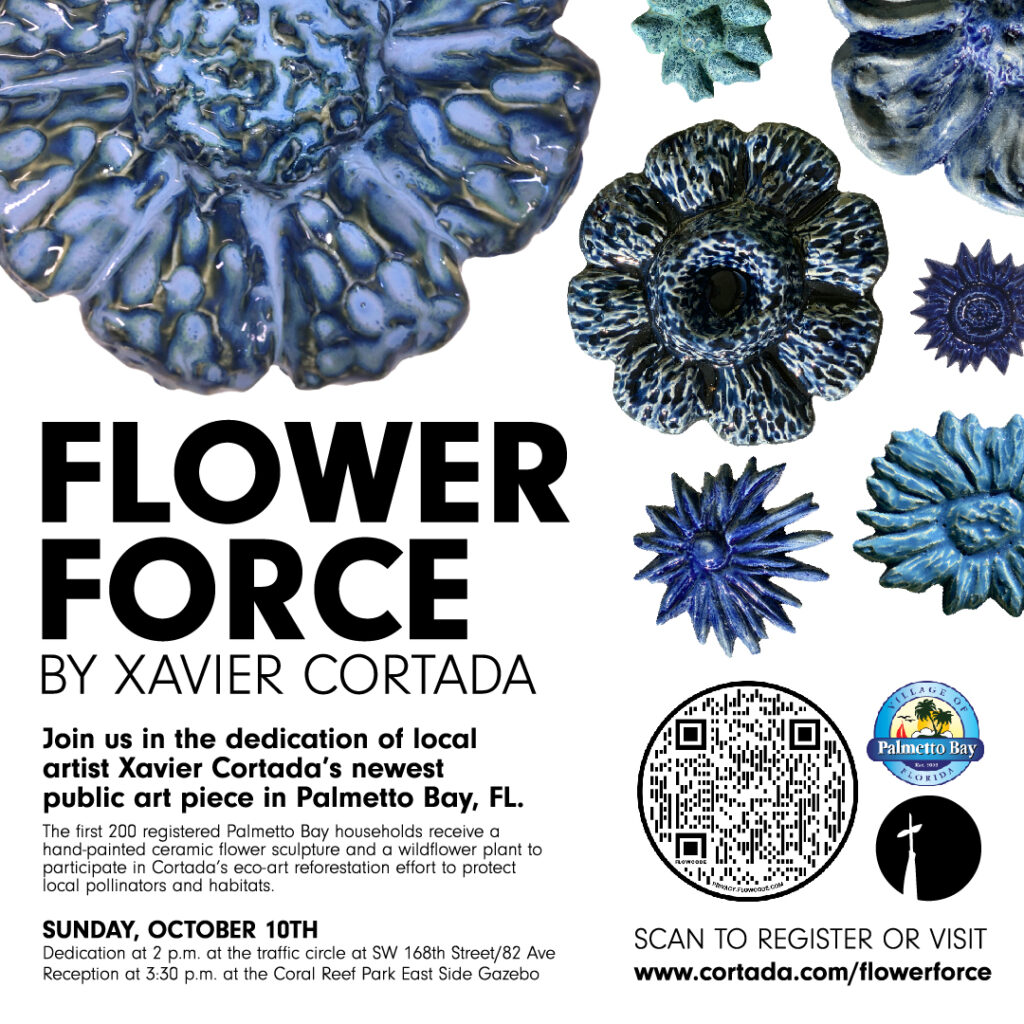

Xavier Cortada, “Flower Force,” hand painted ceramic and tile, 8′ x 4′ x 4′, 2021.

The Village of Palmetto Bay commissioned Xavier Cortada to create a sculpture of a sphere clad in ceramic flowers for the traffic circle on 168th Street and SW 82nd Avenue. The site of this public art piece is on the historic hunting grounds of the Tequesta people who lived a mile to the east, along the water’s edge. In 1513, conquistadores claimed the peninsula for Spain and named it La Florida – from flor, the Spanish word for flower.

That encounter with Western colonizers five centuries ago initiated a series of actions that forever changed our state and its ecosystems. On July 17, 1821, Spain formally transferred Florida to the United States. Since then, we have continued to transform our landscape. Slowly at first, but then almost irrevocably after the industrial revolution and during the twentieth century (destroying wetlands, bulldozing forests, and exploiting natural resources to meet our insatiable need for development). The Flower Force sculpture was built at a traffic circle to harken to the times when the peninsula’s residents lived in tune with nature.

To activate this public art commission, Cortada, in conjunction with the Village of Palmetto Bay’s Art in Public Places program, is inviting 200 of his Palmetto Bay neighbors to be part of the Flower Force. Using the public art piece as the heart of the Flower Force initiative, 200 Palmetto Bay households will receive one of Cortada’s ceramic flowers to install outside of their home as they plant a new native wildflower garden in their yard. Through this process, an ecological restoration effort will radiate from the flower sphere at the traffic circle in Palmetto Bay and extend to the rest of the state.

participatory component

Objectives and Rationale:

“Flower Force” uses my social art practice, the 200th anniversary of the transfer of Florida from Spain to the U.S. on July 17, 1821, and a traditional public art sculpture and garden as points of departure. The idea is to use art’s elasticity to connect present day residents with those who lived in our neighborhoods through time and plan and plant a better future for those who will follow.

With the signing of the Adams-Onís Treaty, my neighborhood, the Village of Palmetto Bay and the rest of Florida became a part of the United States in 1821. Palmetto Bay’s shoreline includes Deering Estate, site of archaeological findings that reveal this area could have been one of the largest indigenous population centers in southeast Florida. Obviously, all that changed in 1513 when Juan Ponce de Leon sailed by in three galleons moving south after making landfall halfway up the peninsula which he claimed for Spain and named it La Florida – from flor, the Spanish word for flower. That encounter with Western colonizers five centuries ago initiated a series of actions that forever changed our state, its governance, its population and its ecosystems.

On July 17, 1821, Spain formally transferred Florida to the United States. Since then, we have continued to transform our landscape. Slowly at first, but then irrevocably after the industrial revolution and during the twentieth century. We’ve drained the Everglades, dredged beaches, paved roads and planted monocultures where there was once wilderness. We’ve redistributed waterways, poisoned rivers, and infiltrated aquifers with salt water. We’ve watched politicians rise to power and deny the human impacts on the largest threat we now face: global climate change and sea level rise.

On this 200th anniversary, I want us to reflect on all of this and try to ameliorate the situation. The participatory eco-art project aims to engage 200 Village of Palmetto Bay households in a community-wide public art installation of wildflower sculptures and gardens. By planting wildflowers in residential nodes, the conservation effort will activate a sculpture and engender discussions in the public sphere aimed at saving pollinators, transforming lawns into gardens that conserve water, decreasing the use of pesticides and protecting ecosystems across our community.

I will soon have completed the sculpture at the traffic circle at the center of the village and former hunting grounds by the Tequesta People. This will be the epicenter of the engaged effort: We will distribute a ceramic sculpture and wildflower seeds to all participants. The project’s 200 participating households will dedicate the public art sculpture garden and their residential gardens 200 years after the wilderness where their homes and the traffic circle now sit was “transferred” to our nation.

Innovation:

In my socially engaged art practice, participants are incorporated into problem solving aspects of the work. I first engage them by reframing the way the individuals see themselves in context of one another and the natural world. Through a process of working and learning together, I invite participants to discover themselves as the protagonists of their future. By participating, their curiosity is piqued. The project emboldens them to become eco-emissaries who engage others to help them in continuing to address the very concerns they were first preoccupied with. In essence, it builds community.

In this case, working through the “Flower Force” project, I aim to ask 200 participants who drive by a public artwork in a public space every day and replicate it as 200 smaller private gardens and sculptures in their homes across the community. Conceptually, I am trying to connect the individual (small private sculpture & garden at their home) to the public (large public sculpture and large garden) and in that effort to each other (the other 199 original participants plus those who will follow). At first, I prompt action by making the engagement a selfish one; Participants get a $100 ceramic piece plus wildflowers all for free. While this is an effective strategy for promoting involvement from its participants, it also allows for a process and sense of self-realization from its participants that permeate into collaborative efforts that are driven by that sense of community.

Background:

The original rendition of “Flower Force” in 2012 was designed as a participatory eco-art project using tiled paper drawings and flower seeds. Here, in its latest evolution, I focus on a public place in a neighborhood as the point through which to draw in 200 participants who will look at their lives in the continuum of time (history of the indigenous people who hunted there for thousands of years, the colonizers who impacted the land over the past 5 centuries, and the moment when the land became part of our nation). Conceptually, it also draws them together across space – connecting that public art piece/garden at the traffic circle to the private one at their home. It reorients them as problem-solvers who through their restorative gardens will begin to correct the degradation (development) that has occurred on that space through time. This engaged component is fundamental to my work and to my role as artist who wants to model how to transform the traditional role of artist beyond one who excels at his/her/their craft into an effective community leader/problem solver.

Methodology:

Using the public art piece as the heart of the Flower Force initiative, 200 Palmetto Bay households will receive one of my ceramic flowers to install outside of their home as they plant a new native wildflower garden in their yard. Through this process, an ecological restoration effort will radiate from the flower sphere at the traffic circle in Palmetto Bay and extend to the rest of the state.