Eco-Now

August 10, 2012

Interview by Daniel Hudon

Xavier Cortada is a Miami artist who has created eco-art installations at the North and South Poles and many places in between to explore how humans relate to the natural world. He has worked with groups globally to produce numerous collaborative art projects, including peace murals in Cyprus and Northern Ireland, child welfare murals in Bolivia and Panama, AIDS murals in Switzerland and South Africa, and eco-art projects in Taiwan, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Holland and Latvia. He kindly agreed to answer some of my questions over Skype.

Cortada reclaiming the North Pole for nature.

Cortada reclaiming the North Pole for nature.

Daniel Hudon In 2007 you planted a replica of a mangrove seedling in the moving ice sheet of Antarctica where over the course of 150,000 years it will journey to the seashore where it can theoretically set its roots. In 2008, you planted a green flag at the North Pole to encourage reforestation in the world below. What inspired you to go to the poles for your work?

Xavier Cortada I’m interested in using art to engage, to change the way people see themselves by creating ritualistic installations. At the South Pole, all the longitude lines converge – these are the man-made coordinates for dividing Earth into 24 times zones and here they converge, effectively showing us that we’re all inter-connected. What happens in one part affects what happens in another. The poles are also where we’re seeing the most global warming; this is the proverbial canary in the coal mine.

I planted the mangrove replica on the moving ice sheet to get at the idea of long time. Humans have a certain arrogance and though we have populated all the other continents for thousands of years, we’ve had a permanent presence at the South Pole for only 50 years. Meanwhile, this mangrove seedling is traveling 10 meters per year and in 150,000 years it will travel 1500 Km and reach the nearest shore and “set root” as it were. I contrasted this with flags in the colors of the spectrum with milestones of world history – the Eagle has landed, the fall of the Berlin wall and so on, 50 events in total – so that people can see that these 50 events as 50 flags, stretched (10 meters apart) over 500 meters on the ice, happen in the blink of an eye. Really, it humbles us and reaffirms the notion that we’re simply custodians who must learn to live with nature.

The next year, I traveled to the North Pole and planted a green flag, which said, “I hereby reclaim this land for nature.” As the Arctic sea ice melts, nations clamor to raise their flags over newly open waters to claim the natural resources that lie beneath them — oil, manganese, diamonds, fish – and to control shipping lanes. In addition, rising sea levels threaten the world below. So this was a signal for people to join me in a global restoration effort and keep the pole frozen. For this project, I was asking future participants to plant a native tree in their yard as well as a green project flag and state what the says I hereby reclaim this land for nature. The idea was to use the green flags as catalysts for conversations with neighbors who will then be encouraged to join the effort and help rebuild their native tree canopy. As you know, reforestation reduces the greenhouse gases that cause global climate change. Ideally, as you watch your tree grow, your interest in environmental advocacy will also grow.

The next year, I traveled to the North Pole and planted a green flag, which said, “I hereby reclaim this land for nature.” As the Arctic sea ice melts, nations clamor to raise their flags over newly open waters to claim the natural resources that lie beneath them — oil, manganese, diamonds, fish – and to control shipping lanes. In addition, rising sea levels threaten the world below. So this was a signal for people to join me in a global restoration effort and keep the pole frozen. For this project, I was asking future participants to plant a native tree in their yard as well as a green project flag and state what the says I hereby reclaim this land for nature. The idea was to use the green flags as catalysts for conversations with neighbors who will then be encouraged to join the effort and help rebuild their native tree canopy. As you know, reforestation reduces the greenhouse gases that cause global climate change. Ideally, as you watch your tree grow, your interest in environmental advocacy will also grow.

Daniel: Not many people have been to both poles. What was your experience like at each?

Xavier: I felt very lucky. Many people suffered and died to get to each of these places and I just took a three-hour plane ride from Ross Island to the South Pole. On the “journey,” I drank fruit juices and ate chocolate bars. When I got to the South Pole I was in awe for the historic meaning of the place and had an adrenaline rush for all the installations I was going to do in a short time. It was an exhilarating journey and it strengthened my resolve for the Endangered World Project.

My partner, Juan Carlos Espinosa, came with me to both poles and at that time our state wouldn’t allow us to get married (it still doesn’t), so we exchanged wedding bands at the North Pole – we’ve been to the top and bottom of the world together. Our rings are inscribed 90 N on one side and 90 S on the other side. So the poles inspired art and the inscription inside our wedding bands!

Daniel: On those expeditions you also began your Endangered World project. How did you first tune into the biodiversity crisis?

Xavier: I could see the changes. I remember canoeing with my biology professors across the Everglades, snorkeling with my fraternity brothers in the Florida Keys and seeing the coral get bleached more and more as the years went on.

Daniel: How did participatory art become your forte?

Xavier: I come from a social justice background. Participatory art grew out of seeing art as a vehicle to communication. I organized collaborative murals to give voice to those at society’s margins. Whether it was gang members in Northern Philly or street children in Bolivia — art became an instrument for problem solving. I’ve always wanted my art to be inclusive so that I’m working with the viewer to help change attitudes.

Sometime ago I started painting mangroves. Here in South Florida, they’ve given way to sea walls and development, but they’re important because they create an interface between land and water where marine life can take hold. Small fish find refuge from predators in their intricate roots, which also serve to protect the shoreline from erosion during hurricanes.

After that, I started putting mangrove seedlings in plastic water-filled cups and hanging them in the windows of retail shops on South Beach where they would have grown if we hadn’t destroyed their habitat. These vertical nurseries served not just to nurture the seedlings for future planting along Biscayne Bay but also invited passersby to join the Reclamation Project (www.cortadaprojects.org/archives/reclamationproject) and participate in the reforestation. I’m not trying to be alarmist, instead, I don’t want you to lose hope that you can do something.

Cortada’s Endangered World Installation at the South Pole

Cortada’s Endangered World Installation at the South Pole

Daniel: As you planted the endangered species flags around the South Pole, did you feel connected to the world above you and to these species? What were your thoughts?

Xavier: Planting the 24 flags of endangered species [one for every 15 degrees of longitude] at the South Pole was almost like exiling them – they are in peril and I am serving notice that I understand. I was creating a testimony through a ritualistic installation.

Daniel: What about at the North Pole?

Xavier: I’d brought 360 white flags, one for each degree of longitude, with the name of an endangered species to be handwritten on each, but the flags were confiscated at the port city of Murmansk [read details about the irony of surrendering white flags here]. I guess the Customs official thought I could sell them. Anyway, I still had a large canvas so I hand-wrote the names of all 360 species on a circle on this canvas and at the North Pole spoke the degree and names of each endangered animal to each degree direction where they live. It was ritualistic. I was standing on the thinning sea ice (we’d traveled by icebreaker and because of global warming we made the journey in only five days – record time – because of the thinning ice; usually it takes a few days longer) and recognizing the peril that these animals are in. Saying the name of something is valuable. I felt a connection as I spoke to each – from that one location I could connect to all 360 different habitats. At the end of the decade some of these animals may no longer exist. For example, we’ve already lost the Yangtze River dolphin. So in saying the names I was saying to the animal that I’m going to wage this campaign for you – we’re not forgetting you, we’re going to try some bio-remediation before it’s too late. With actions and words together it was trying to use art to keep the animals alive.

Cortada’s Endangered World Installation at the North Pole

Cortada’s Endangered World Installation at the North Pole

Daniel: How did you make this a participatory installation?

Xavier: Well, first let me tell this story that before leaving the North Pole I took a chunk of ice and on the ship I asked the chef to serve it to everyone as part of a performance art piece: The North Pole Dinner Party. In it, my fellow passengers consumed the North Pole. They understood that it’s something worth fighting for [keeping the North Pole frozen] because it’s now part of them.

The South Pole has a treaty, but who owns the North Pole? It’s just frozen water. Political powers shouldn’t be so eager to plant their flag at the North Pole – if it stays that way [frozen] then no country wants it, but if the pole thaws, then countries will want to exploit it, open shipping lanes and so on, as I mentioned. I wanted to create a piece at the North Pole that reclaimed it as a real – not symbolic – gesture. So I planted a green flag to encourage reforestation in the world below. Planting more trees will sequester more carbon and thus keep the North Pole frozen. The green flag is symbolic of our commitment to reducing our footprint. If we create this movement and plant both a green flag and a tree, we’ll create a world of North Pole citizens who will work to keep the North Pole frozen.

I then took the 360 degree longitude locations [the Endangered World installation] and wrote them on 360 bricks and made a brick wall and installed it in Borger, in the Netherlands. This is in the Drenthe province, where Van Gogh painted the potato eaters and where there are many hunebeds, or graves, that were built in 3500 BC from boulders left behind by the receding glaciers of the last ice age. The brick wall forms a portal for one of the graves. The animals are part of an interconnected web that includes us humans. How many can go extinct before the door crumbles and the grave is revealed?

The Life Wall

The Life Wall

But it’s called the Life Wall – my work is full of hope. By acting locally we can have a global impact. You can adopt one of the species on the Life Wall and pledge to engage in an eco-action. Just get a small stone and write the longitude of your adopted animal on it and that stone will remind you of your eco-action. The idea is to create eco-emissaries who will act as agents for good. You pay with your actions, that’s what brings you into the conversation so that we can see ourselves in new ways. The solution lies in consuming less and we get there through advocacy and awareness.

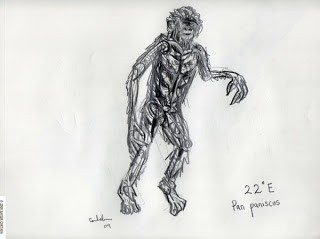

Endangered World had another iteration as 80.15 W, which is the longitude of Biscayne National Park. There I made drawings on carbon paper, a metaphor for the impact or carbon footprint that humans have on that animal, including the 17 endangered species from the park.

In 2009, I posted 180 drawings of the animals featured in his Endangered World installation on Facebook. These pencil drawings portrayed animals struggling for survival in the Eastern Hemisphere (Longitude: 0 degrees to 179 degrees East). I changed my profile image every day to one of these drawings to say, “I am this endangered animal. I am this endangered fish. I am this endangered mammal.” Because we are all interconnected. What endangers one species affects all, including our own. That’s my point: We are all inter-connected. The more we think in silos the more we do so at our peril. My work is about blurring lines and finding commonality.

Biscayne National Park

Biscayne National Park

Daniel: What do you say to people who argue that there’s a techno-fix to our environmental problems?

Xavier: My goal is to create eco-emissaries to become an intelligent part of the dialogue. The solutions are for consumers to lower their consumption – anyway, consumption makes us feel hollow inside. Having more only makes you want more.

People need to take responsibility. As I said above, when you plant a green flag next to a tree, as your tree grows so will your advocacy. It’s about you acting and engaging, not just awareness. I want to create a dialogue so people will fall in love and commit to doing something.

After the election in 2008, there has been no real discussion about global warming because everyone was focusing on the economy and not realizing the environment poses a greater threat. With the BP disaster in 2009 another opportunity was lost. These have just strengthened my resolve to create more eco-emissaries. We need more sustainable practices. For instance, through our monoculture we’re destroying forests growing plants whose properties we don’t yet know. It may be efficient for agriculture for this season’s food needs, but at what cost to future generations.

Daniel: What sort of response have you had to your eco-art and what can we look forward to in the future?

Xavier: Juan Carlos Espinosa and I were invited to spend this summer as artists-in- residence at the White Mountains National Forest (see whitemountaintrailmix.wordpress.com). There, Icreated works about time, space and species in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. I worked with scientists to understand how global warming is affecting two species of butterfly and the Bicknell’s thrush. The White Mountain Arctic (Oeneis melissa semidea) and the White Mountain Fritillary (Boloria titania montinus) are glacial relics. These butterflies evolved as subspecies at the mountain’s alpine elevations after the glaciers receded. Scientist’s have yet to discover the plant the Arctic Butterfly uses to lay its eggs, so it is difficult to gauge potential global climate change threats.

The Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) only summer habitat is below the alpine area in White Mountain National Forest, a habitat shrinking as global climate change allows hardwoods to encroach from below and high winds at the alpine elevations restrict the upper boundaries of their dense Balsam Fir habitat. This bird species migrates to habitats beyond the forest boundaries, wintering on the island of Hispaniola, where its habitat is being deforested. Researchers are focused on the effects of acid rain and the deposition of mercury at the top of WMNF mountains as possible causes for dwindling species population.

In terms of response, Native Flags has been very successful: 750 trees planted in St. Petersburg and all 336 schools in Miami for three years in a row have planted a green flag and a tree on Earth Day. You can read about the 360 Eco-actions that have been adopted for the Endangered World installation. This year, we’re going to plant 500 wildflower gardens to recreate Florida’s biodiversity of 500 years ago when Juan Ponce de Leon first landed. In the summer, we’ll distribute 900,000 native wildflower seeds to plant across the state. I’m now Artist in Residence at Florida International University’s College of Architecture and The Arts. That’s where I’ve based my community arts practice. Through my office (Office of Engaged Creativity) I have the potential of reaching and engaging 40,000 students!

Daniel: I hope you can create 40,000 or more eco-emissaries, we need them!

Xavier: As I said I’m just trying to create a dialogue so that people will fall in love with the natural world and commit to doing something. So thanks for creating this dialogue with me so that I can share my work.

For more information: http://cortada.com

Cortada’s sketch of the bonobo, endangered.

Cortada’s sketch of the bonobo, endangered.