Street Miami

July 20, 2001

By Emma Trelles Photos by Richard Patterson

Urban: of, relating to, characteristic of, or constituting a city.

— New College Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Through Art and Art only that we can shield ourselves from the sordid perils of actual existence.

— Oscar Wilde

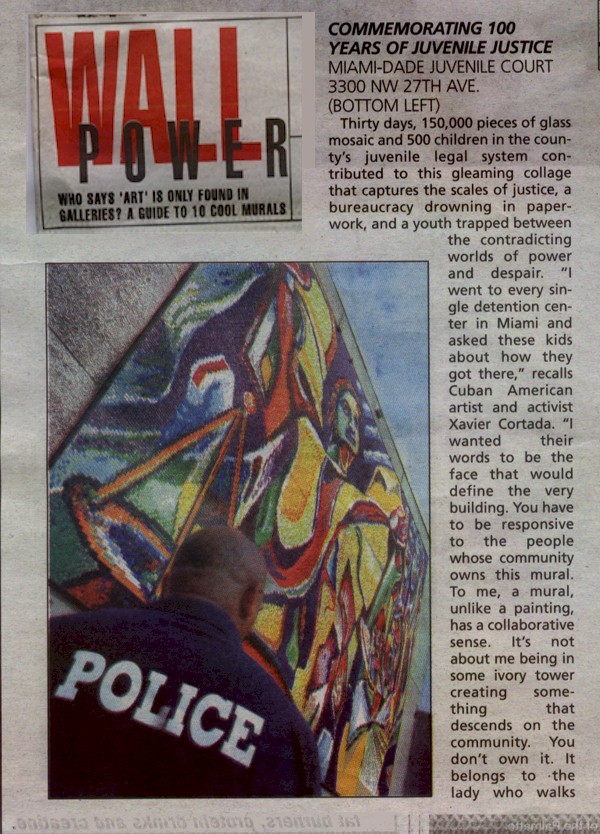

Urban murals are hardly new. Mexico’s Mayans and Aztecs painted their temple and palace walls with images of kings and gods. During this country’s Depression, muralists like Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco inspired and taught government-hired artists to transform the walls of federal buildings and libraries into canvases. In the mid-’60s, artists in Chicago painted the “Wall of Respect” in the city’s South Side, and similar murals began appearing in black communities around the country. Today, Hispanic communities are largely responsible for the more than 1,000 public murals found within Los Angeles and southern California. In Miami’s poorest and roughest neighborhoods, we found the unexpected: pockets of beauty in the guise of painted concrete islands, industrial walls thick with both rich and sun-shorn color. These murals were mildly entertaining at worst and eye-widening when at their best. They chronicle a time and community that might otherwise be overlooked because they are more than art. Murals are artifacts, storytellers, preservers of myths and truths. We found 10 murals that engaged us, and we started asking questions. Here’s what we found:Commemorating 100 Years of Juvenile Justice Miami-Dade Juvenile Court 3300 NW 27th Ave. Thirty days, 150,000 pieces of glass mosaic and 500 children in the county’s juvenile legal system contributed to this gleaming collage that captures the scales of justice, a bureaucracy drowning in paperwork, and a youth trapped between the contradicting worlds of power and despair. “I went to every single detention center in Miami and asked these kids about how they got there,” recalls Cuban-American artist and activist Xavier Cortada. “I wanted their words to be the face that would define the very building. You have to be responsive to the people whose community owns this mural. To me, a mural, unlike a painting, has a collaborative sense. It’s not about me being in some ivory tower creating something that descends on the community. You don’t own it. It belongs to the lady who walks her dog by that wall every day.”