May It Please the Court

a solo exhibit by Xavier Cortada

in the rotunda of the Florida Supreme Court

Tallahassee, FL

Opening reception: March 1st at 3 p.m.

Exhibit runs through July 15, 2004.

Presented by the Florida Supreme Court, Arts in the Court Committee

see article | see “Painting Constitutional Law” (2021)

Virtual Exhibit: The Rotunda

Xavier Cortada painted this series for “May It Please the Court,” a solo exhibit in the rotunda of the Supreme Court of Florida. The paintings portray landmark US Supreme Court cases originating in Florida, the artist’s home state. The paintings, which remained at the Supreme Court through 2009, are now on long term loan to Florida International University College of Law.

Gideon v. Wainwright

48″ x 36″

oil on canvas, 2004

on long term loan to the Florida Supreme Court

Palmore v. Sidoti

48″ x 36″

acrylic on canvas, 2004

on long term loan to the Florida Supreme Court

The Miami Herald Publishing Company v. Tornillo

48″ x 36″

oil on canvas, 2004

on long term loan to the Florida Supreme Court

Gideon v. Wainwright

48″ x 36″

oil on canvas, 2004

on long term loan to the Florida Supreme Court

Seminole Tribe v. Florida

48″ x 36″

acrylic on canvas, 2004

on long term loan to the Florida Supreme Court

Williams v. Florida

48″ x 36″

acrylic on canvas, 2004

on long term loan to the Florida Supreme Court

Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye

v. City of Hialeah

48″ x 36″

acrylic on canvas, 2004

on long term loan to the Florida Supreme Court

All are equal (1),

but some are more equal than others (2)

48″ x 144″, mixed media on canvas, 2002

(1). Dade County Human Rights Ordinance is enacted, January 18, 1977.

(2). Dade County Human Rights Ordinance is repealed, June 7, 1977.

Virtual Exhibit: Entrance to Chambers

Xavier Cortada (with youth at TGK adult jail)

convictim, 60″ x 144″, mixed media on canvas, 2001.

(On loan from of the Law Offices of Bennett Brummer, Public Defender)

Virtual Exhibit: Judicial Meeting Room

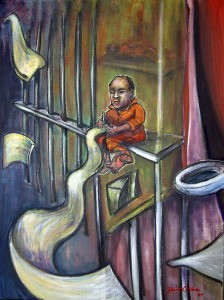

Xavier Cortada (with youth at Citrus residential program),

Trapped

48″ x 60″, mixed media on canvas, 2002

(On loan from the Children and Youth Law Clinic of the University of Miami School of Law)

Xavier Cortada (with youth at the Jackson Memorial Hospital SIPP residential program),

The Voice Project 2003 Mural

48″ x 60″, mixed media on canvas, 2003

(On loan from the Children and Youth Law Clinic of the University of Miami School of Law)

Florida Supreme Court Justices Barbara J. Pariente and Raoul G. Cantero, III talk with Xavier Cortada in front of the artist’s Proffitt v. Florida painting during the March 1, 2004 opening reception of the “May It Please the Court” exhibit in the rotunda of the Supreme Court, Tallahassee, Florida.

Florida Supreme Court Justice Peggy A. Quince listens to Xavier Cortada as he describes his All are equal1, but some are more equal than others2 mural during the March 1, 2004 opening reception of the “May It Please the Court” exhibit in the rotunda of the Supreme Court, Tallahassee, Florida.

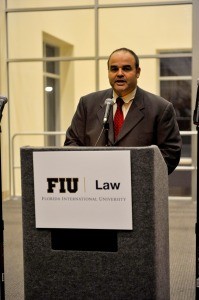

On January 16th, 2010, Xavier Cortada joined Dean Acosta and President Rosenberg in presenting his May it Please the Court exhibit at FIU.

On January 16th, 2010, Xavier Cortada joined Dean Acosta and President Rosenberg in presenting his May it Please the Court exhibit at FIU.